Quite apart from a huge humanitarian disaster there is a disaster for the planet. From being a carbon sink an Amazon rain forest in drought turns into a source of carbon - a postive feedback

Reservoir

at 5 Percent Capacity: Climate Change to Leave Sao Paulo’s 20

Million Without Water By November?

13

October, 2014

Suffering

from its worst drought in over 84 years, the city of Sao Paulo is in

the midst of a crisis. For as of this weekend the city’s primary

reservoir — the Cantareira — had dropped to just 5 percent

capacity putting millions at risk of losing access to water.

The

fall prompted the city’s governor — Geraldo Alckmin — to again

ask for permission to draw emergency water supplies from below flood

gates to alleviate catastrophic losses from the Cantareira and ensure

water supplies to the region’s 20 million residents. The move would

tap a river system that feeds two other states also facing water

shortages — Rio de Janeiro and Minas Gerais. But the draw is

only a temporary stop gap and, without rain, the Cantareira will

continue to fall — bottoming out sometime this November.

(Dam and section of Cantareira Reservoir high and dry under incessant drought conditions. Image source: Linhas Populares.)

Don’t

Use the ‘R’ Word

The

Cantareira provides water to nearly 50 percent of Sao Paulo’s

residents. But ever since February of 2014 the multi-year long

drought, a drought that has featured less and less seasonal rainfall

over time, has triggered reduced water access by city and state

residents.

Those

living within areas served by the Cantareira have been treated to

increasing periods of dry taps — being forced to go for longer and

longer without available water supply. The intermittent lack of water

service has put a strain on businesses and residents alike with many

people living in Sao Paulo being forced to abstain from washing,

cooking and brewing. For now, water for drinking can be stored during

times when the faucets flow. But that time could come to an end all

too soon without a change in the weather.

“Sometimes

I have no water for two days, then it comes back on the next day and

the day after that, I have no water again,” said Zeina Reis da

Cruz, a 55 year old resident of one of Sao Paulo’s lower income

neighborhoods in a September 25 interview with The

Globe and Mail.

Despite

an ongoing and growing failure to provide water services, the city

refuses to use the word ‘rationing.’ Such an admission of failure

would have weighed heavily on Alckmin’s re-election campaign

(Alckmin was just recently elected to a new term as governor).

Instead, irate citizens and businesses making calls to utilities are

simply told that there is nothing wrong with the water supply and to

wait until the water comes back on.

Regardless

of politically-motivated denials, water rationing is the most

accurate way to describe what many Sao Paulo residents have been

experiencing for 9 months now under a regime of systemic drought that

just grows steadily worse with time.

Climate

Change Spurred by Deforestation, Worsened By Atmospheric Heating

The

great forest of the Amazon provides a rich source of water for both

Brazil and surrounding countries. It captures as much as 80 percent

of the tropical atmosphere’s heavy moisture load and re-circulates

it locally – providing ongoing and consistent rains. A critical

means of replenishing regional water sources.

But,

over recent decades, a combination of clear cutting and human-spurred

warming of the climate have been adding severe stresses to the

Amazon. During

the period of 2000 to 2010, the great rainforest lost 93,000 square

miles of wooded land alone to clear cutting.By

2014, government restrictions had brought down the rate of loss to

around 2,300 square miles per year, but by this time

warming-related impacts to the Amazon were looking even more dire.

As

the 2000s progressed, it was becoming ever-more-clear that a heating

climate driven by human fossil fuel emissions was taking an

increasing toll. For, during recent decades, the

Amazon has been warming at a rate of around 0.25 C every ten years —

about twice as fast as the global climate system. The added heat

increased evaporation, pushing soil moisture levels below critical

thresholds.

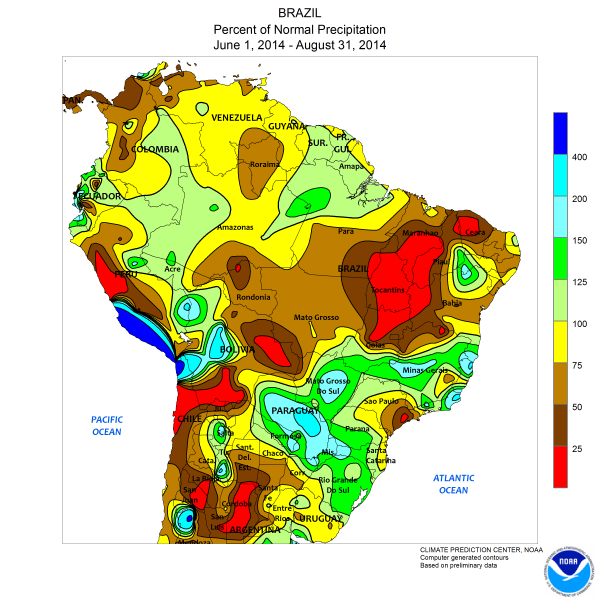

(It’s not just Sao Paulo, most of South America is showing ongoing rainfall deficits. Map provided by NOAA shows percent of normal precipitation received by South America this summer. Note the severe drying over much of the Amazon Rainforest and broader South America coupled with drought over Sao Paulo. Image source: Climate Prediction Center.)

This

loss has, in turn, increased the prevalence of forest-destroying

understory fires. And,

according to a 2012 NASA study these understory fires have been

burning away the Amazon at the rate of more than 30,000 square miles

every ten years for nearly two decades. By late this

Century, business

as usual fossil fuel emissions and related warming of 4 degrees

Celsius is expected to destroy about 85 percent of the Amazon,

resulting in widespread desertification of a once-lush region.

Today,

this period of initial drying caused by a human heating of the

atmosphere appears to be putting the stability of Brazil’s most

populous city at risk.

A

Major Humanitarian Disaster

Typically

for October, Sao Paulo receives between 80 and 100 mm of rainfall. So

far this month, the number is approaching zero. Long

range forecasts bring that total to just above 50 mm through

the end of the month — about half the usual rainfall. Very dry for

a month that is supposed to be the start of Sao Paulo’s rainy

season, a period that usually runs from October through March. A

rainy season once fed by a now greatly endangered and increasingly

moisture-impoverished Amazon rainforest.

It

would take a massive rainfall to replenish Sao Paulo’s reserves.

The kind of rain event that would result in widespread devastation

should it emerge. Now, city officials appear to be holding out for

any rain to tip the scales on their swiftly shrinking water stores.

But

if the worse happens. If this year is a repeat of last year which saw

a parched rainy season. If the rains of October and November continue

to delay or do not emerge at all, then Sao Paulo faces a terrible

event. A complete drying out of its largest water store and a

complete cut-off of water supplies for millions of residents.

“It

will be a real humanitarian disaster if it happens. We are 20 million

people: You can’t bring water on trucks for 20 million. So they are

praying that rainfall will come – but it may not rain so much.”

Links:

(Hat

tip to Andy)

(Hat

tip to Colorado Bob)

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: only a member of this blog may post a comment.